Last Sunday I went down to Dealey Plaza, not so much to have Kennedy assassination author Robert Groden solve the mystery of the assassination for me as to have him solve the mystery of life. That’s the one that gets me.

It was a gorgeous day. The sun was soft. A mild breeze rumpled the leaves. Fifty-four years after the fact, people stood with arms akimbo on the sidewalk overlooking the X that marks the spot where John F. Kennedy was shot, still debating in muted voices and nods the one thing we all know we may never know – what really happened.

Walking out over the grass on my way to find Groden, I thought of something said to me seven years ago by Conover Hunt, who helped design the Sixth Floor (Kennedy assassination) Museum in the late 1980s. She was talking about Dealey Plaza specifically but also about all of the great battlefields and scenes of tragedy that are now historic sites:

“These places are like debate parks,” she said, “where you can engage in the discussion and feel the power of history under your feet.”

Actually I think of her words every time I drive by Dealey Plaza, whether it’s crowded with tourists in nice weather or stalked on cold wet days by a few lonely seekers. Her point was that these great scenes of national pain, now public parks, are not places we go to settle a point. We go there as she said so eloquently to feel history beneath our feet, to be in it and to own it, to let our souls sing Woody Guthrie’s song, “This land is my land,” or, like Ratso Rizzo in the 1969 film, Midnight Cowboy, to tell the gods of destiny, “Hey, I’m walkin’ here!”

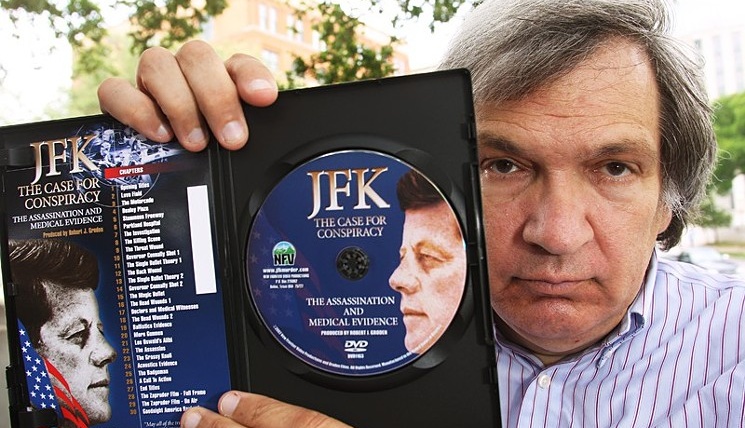

I had three reasons for seeking out my old friend Groden. Make that four. The first was immediate and local. He had left me a voice message saying that after a seven-year battle he finally settled his lawsuit against the Sixth Floor for conspiring to abridge his civil rights. Groden has accused the Sixth Floor of working with City Hall to force him to stop coming to the plaza every weekend to expound his theory of the assassination of Kennedy on Nov. 22, 1963.

Whatever you may think of his theory of how the assassination happened (multiple shooters from the front), there is no debating what the Sixth Floor and City Hall have done to Groden himself. Often at the behest of the museum, which occupies the School Book Depository Building adjacent to the plaza, the city has ticketed, arrested and even jailed Groden 82 times over the years for lecturing and selling books from a small folding table in the plaza.

In 82 of those cases – yes, that would be all of them – the city has been tossed out of court, usually by its own municipal judges, always for the same singular and consistent reason. It’s not against the law to lecture and sell books from a small folding table in Dealey Plaza.

During this entire saga, Groden has been brilliantly represented by an attorney, Brad Kizzia, whose consistent triumphs over the city and the museum must go down as one of the great defenses of free speech in this country.

Make no mistake. That’s what this is about. All of the reasons for persecuting Groden over these years have been the same reasons free speech is attacked anywhere in the world. Groden makes powerful people angry.

Groden’s insistent message has always been that the Kennedy assassination was the product of a larger conspiracy and is a mystery that remains unsolved. Old-guard rich people in Dallas hate that story from the hair on their withered heads to the tips of their crustaceous toenails. And over the years I have stopped blaming them for it. I guess if I grew up getting blamed for an assassination I didn’t do, I might be pretty crustaceous about it myself by now.

But it’s that very kind of speech, Groden’s kind, speech that makes powerful people angry, that is the most susceptible to attack, the hardest to defend and the most crucially important to the survival of democracy. I see him as my brother in arms.

Groden and I are in the same army, but he’s the guy up in the trenches dodging mortar rounds and gas attacks. I do my fighting a few miles back, from a small table in front of a smart little café while savoring the day’s first well-frothed latte and listening to a guy in a beret down the block softly playing the accordion. I don’t really want to trade places with Groden, because … what about my latte? But I do admire him enormously.

He was at his own table Sunday with a small crowd gathered ‘round, some of them fingering through the display of tapes and books. I waited for a break and then congratulated him on settling with the Sixth Floor.

“You know what they say about a bird in the hand being worth two in the bush,” he said. “Well, this would have been worth a lot more in the bush, but I would have had to go through one or two trials, and there was no guarantee. So essentially, they have promised they would leave me alone, and I took much less than it was worth. Hopefully they will have buried the ax, as it were, and not in my head.”

As if apologizing, he reminded me that his health has not been great. He’s 70. “You know I’m going blind in one eye,” he said. “I had a stroke in my right eye, and I lost 75 percent of the vision in that eye, so anything that frustrates me or adds pressure or aggravation is bad.”

He told me how grateful he is to Kizzia, the lawyer: “Brad did a great job defending me and arguing the case. He spent seven years on it. Without him I would never have been able to get anywhere.”

The second thing I had come to talk to him about was the possible release next October of some 3,600 files related to the original government assassination investigations. I wondered if he thought that would be a big deal.

“I don’t hold out very much hope,” he said. He thinks most of what might be released will be “a ton of stuff that wasn’t important, stuff like [assassin] Lee Harvey Oswald’s mother’s dental records, which wouldn’t matter even if Lee had bitten the president to death.”

He knows what he would like to see: “Some of the stuff like Oswald’s tax records, the connection to the CIA, [the rest of] the autopsy pictures.”

As staff photographic consultant to the U.S. House of Representatives Assassinations Committee from 1976 to 1979, Groden had access to vast inventories and catalogues of evidence. He claims now that 90 percent of the photographs made at Kennedy’s autopsy have disappeared from the National Archives.

Groden was able to “secure” (I don’t ask too much about that) 15 of 152 photos he says he saw catalogued from the autopsy. He has published all 15 over the years.

“I think the most important thing I was able to release was the autopsy pictures,” he said last Sunday. “You can’t look at the president’s head with a bullet entry wound in the right temple exiting the back of the head and think that anything else happened except a shot from the front.”

Actually, I can’t look at the president’s head with an entry wound because I just can’t, but I kept that to myself. My interest in Groden has always been Groden, not the assassination. I do believe in conspiracy. I believe that quantum physics, wave theory and the president’s hair are all part of the same conspiracy, but I know from harsh experience that I can only manage it in measured bites. I’m still working on City Hall.

I had two more things I wanted to talk to him about. Well, tell him, more than talk about. He and I are both old now. You never know when it’s your last chance.

I wanted to tell him that he’s my hero. He’s what counts. I don’t want to say that the Kennedy assassination doesn’t count. It does, of course. And if I said it didn’t, he would never forgive me.

But we live in a universe of Kennedy assassinations. We battle to stay afloat in a dirty sea of official lying, deflection, omission and straight-up two-fisted suppression. We all depend on the front-line soldiers like Groden, less for the specific information they may reveal to us than for the fact that they are up there, hunkered down and obdurate in the trenches, refusing to give ground.

I know this: As sure as I sit here in front of my little café banging out words, if the day ever comes that people like Robert Groden are no longer up there defending the line, that line will come in a heartbeat and find me. I told him something like that Sunday.

He said he hoped he had done some good. “A lot people out there in the plaza are able to get their points across now,” he said, “good, bad or indifferent. Freedom of speech has been defended.”

Finally I asked him the big one. Life.

Without a moment’s hesitation, he said, “Life is like a hot fudge sundae with a cockroach in the whipped cream.”

Oh my God, is that what that thing is? I knew he’d know! I really think everything has finally come together for me. The grand mystery is solved. So … we eat around it, right?